Billy Collins

November 25, 2009

Aristotle

by Billy Collins

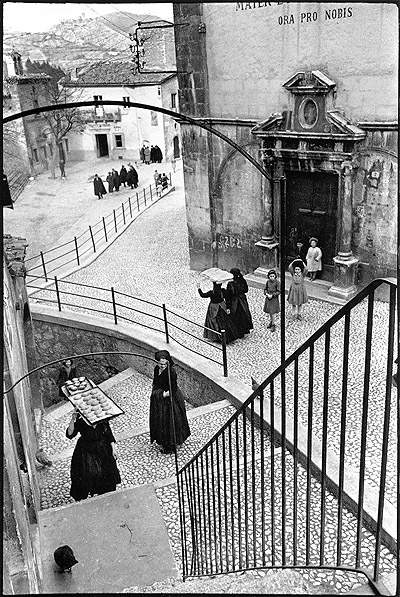

Henri Cartier Bresson

August 27, 2009

A photographer whose work I have newly come to appreciate.

The Searching Artist

August 4, 2009

http://www.davidbazan.com/2009/07/chicago-reader-cover-story/

From Christian naivety to contentment in agnosticism. This is the path of songwriter David Bazan, according to writer Jessica Hopper with regard to his forthcoming album Curse Your Branches, set for release on September 1st, 2009. What struck me most about the article, which pulls a considerable amount of lyrics from the new album, is that it feels like an attempt to categorize the artist as to which side he is on, once and for all. The once man of faith has now crumbled, as if the most important question is to determine his Christianness or un-Christianness. However, I can’t help but disagree that Bazan’s intention with this album was to show his listeners that he is not a Christian, or that his intention is that much different from what he has striven for in the past. I’m reminded of his song “Secret of the Easy Yoke” which was written over a decade ago on Pedro the Lion’s It’s Hard to Find a Friend.

I could hear the church bells ringing

They pealed aloud your praise

The member’s faces were smiling

With their hands outstretched to shake

It’s true they did not move me

My heart was hard and tired

Their perfect fire annoyed me

I could not find you anywhere

Could someone please tell me the story

Of sinners ransomed from the fall

I still have never seen you

And somedays i don’t love you at all

The devoted were wearing bracelets

To remind them why they came

Some concrete motivation

And the abstract could not do the same

But if all that’s left is duty

I’m falling on my sword

At least then i would not serve

An unseen distant lord

If this only a test

I hope that i’m passing

Cuz i’m losing steam

And i still want to trust you

Peace be still

There may be more doubt and more despair on the new album, however, as always, Bazan is searching for answers and is distraught with modern evangelicalism. The artist may have once been a Christian and may now be agnostic, but this really shouldn’t matter, unless your sole purpose for listening to his music is solve the puzzle of his existence. Appreciate his music for what it is: a uniquely honest approach to his personal conceptions of who God is and his struggle with uncertainty.

The Infinite Provisions of the Law

July 15, 2009

Therefore Paul says in another place (I Timothy 1:5), ‘Love is the sum of the commandments.’ But in what sense is this said? It is said in the same sense as saying that love is the fulfilling of the law (Romans 13:10). In another sense the sum comprises all the single commandments, though shalt not steal, etc. But try to find the sum in that way, however long you continue to count, and you will see it is useless labor, because the concept of the law is inexhaustable, endless, and unlimited in its provisions; every provision brings forth a still more exact explication of itself, and then again by reference and relation to the new provision a still more exacting provision, and so on ad infinitum…

Therefore Paul says in another place (I Timothy 1:5), ‘Love is the sum of the commandments.’ But in what sense is this said? It is said in the same sense as saying that love is the fulfilling of the law (Romans 13:10). In another sense the sum comprises all the single commandments, though shalt not steal, etc. But try to find the sum in that way, however long you continue to count, and you will see it is useless labor, because the concept of the law is inexhaustable, endless, and unlimited in its provisions; every provision brings forth a still more exact explication of itself, and then again by reference and relation to the new provision a still more exacting provision, and so on ad infinitum…

So, it is with the law: it defines and defines but never reaches the sum, which is love. When one speaks of a sum, the very expression seems to invite counting, but when a man has become tired of counting and nevertheless is all the more eager to find the sum, he understands that this word must have a deeper meaning…

Under the law man groans. Wherever he looks he sees only demands, never boundary—like one who looks out over the ocean and sees wave after wave, but never a boundary. Wherever he looks he meets only severity, which in its infinitude can always become more severe, never the boundary where it becomes mildness. The law starves out, as it were; one never gets his fill by its help, for its character is precisely to take away, to demand, to exact to the uttermost, and the continuous regression of indefiniteness in the multiplicity of all its provisions constitutes an inexorable collection-statement of demands. With every provision the law demands something, and yet there is no limit to the provisions. The law resembles death. But I wonder if life and death do not know essentially one and the same thing; for just as accurately as life knows everything which life gives life, just so accurately does death know everything which gives life; consequently, there is in a certain sense no quarrel between law and love in respect to knowledge, but the love gives and the law takes, or, to express the relationship more concretely in proper order, law requires and love gives. There is not a provision of the law, not a single one, which love wishes to do away with; on the contrary, love gives them for the first time complete fullness and definiteness. In love all the provisions of the law are even more definite than in the law. There is no quarrel, then, any more than between hunger and the blessing which satisfies it.

Soren Kierkegaard, Works of Love

The Exterminating Angel by Luis Buñuel (1962)

June 19, 2009

Whether you are interested in surrealism in art or cinema or not at all, with a title like this the question may be posed: ‘How could you not want to see The Exterminating Angel?’ Indeed, a considerable explanation will be needed from the refusing skeptic.

Whether you are interested in surrealism in art or cinema or not at all, with a title like this the question may be posed: ‘How could you not want to see The Exterminating Angel?’ Indeed, a considerable explanation will be needed from the refusing skeptic.

Like most of Bunuel’s films, there are numerous ideas looming about concerning human nature, social class and religion. This one is no different in that regard. The concise story line: a high society dinner party upon which, after retiring to the living area, the distinguished guests realize they cannot go home or even leave the room. The reason? There is no reason. Without giving away too much away, these dignified individuals begin lose control over their strange predicament and proceed then to discard honor and dignity, letting out their true selves. Through this destructive process, the viewer begins to see Bunuel’s dark impression of humanity.

Other recommendations by Luis Bunuel: That Obscure Object of Desire, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, Diary of a Chambermaid

The Thankless Task

June 16, 2009

But when you walk with God, hold only to him and understand God within everything you understand; then you will discover—shall I say to your disadvantage—then you will discover your neighbor, since God will constrain you to love him—shall I say to your disadvantage—for loving one’s neighbor is a thankless task!

But when you walk with God, hold only to him and understand God within everything you understand; then you will discover—shall I say to your disadvantage—then you will discover your neighbor, since God will constrain you to love him—shall I say to your disadvantage—for loving one’s neighbor is a thankless task!

Soren Kierkegaard, Works of Love

Grizzly Bear – Veckatimest (5/26/09)

June 9, 2009

Grizzly Bear’s Yellow House was great, Veckatimest is better. Structurally, the album is unrestricted and searching, as it is with one who ventures aimlessly into lush evergreens and stumbles upon something of worth. The Brooklyn-based group appears to do whatever they wish with rhythm and texture, pausing to contemplate the next direction, and then progressing when the answer presents itself. And yet, track for track, each remain beautifully contained.

Opening tracks ‘Southern Point’ and ‘Two Weeks’, while upbeat and certainly noteworthy contributions, are not indications of the sweet-swaying melancholy that the work later becomes. Yes, this slow drawling sound has a sweet, almost positive tone to it. ‘Ready, Able’ is maybe the best example of what the group are capable of. It exemplifies their ability to create and coerce pace with seamless transition. In this gentle dictatorship of sound, both casual and active listeners are free to appreciate.

Grizzly Bear are doing what they want, and doing it very well.

Forsake All Distinctions

June 7, 2009

But God is love; therefore we can resemble God only in loving, just as, according to the apostle’s words, ‘we can only be God’s co-worker’s—in love.’ Insofar as you love your beloved, you are not like unto God, for in God there is no partiality, something you have reflected on many times to your humiliation, and also at times to your rehabilitation. Insofar as you love your friend, you are not like unto God, because before God there is no distinction. But when you love your neighbor, then you are like unto God. Therefore go and do likewise. Forsake all distinctions so that you can love your neighbor.

But God is love; therefore we can resemble God only in loving, just as, according to the apostle’s words, ‘we can only be God’s co-worker’s—in love.’ Insofar as you love your beloved, you are not like unto God, for in God there is no partiality, something you have reflected on many times to your humiliation, and also at times to your rehabilitation. Insofar as you love your friend, you are not like unto God, because before God there is no distinction. But when you love your neighbor, then you are like unto God. Therefore go and do likewise. Forsake all distinctions so that you can love your neighbor.

Kierkegaard, Works of Love